Photoevaporation Shapes Exoplanet Evolution: Study Reveals Birth of Common Worlds

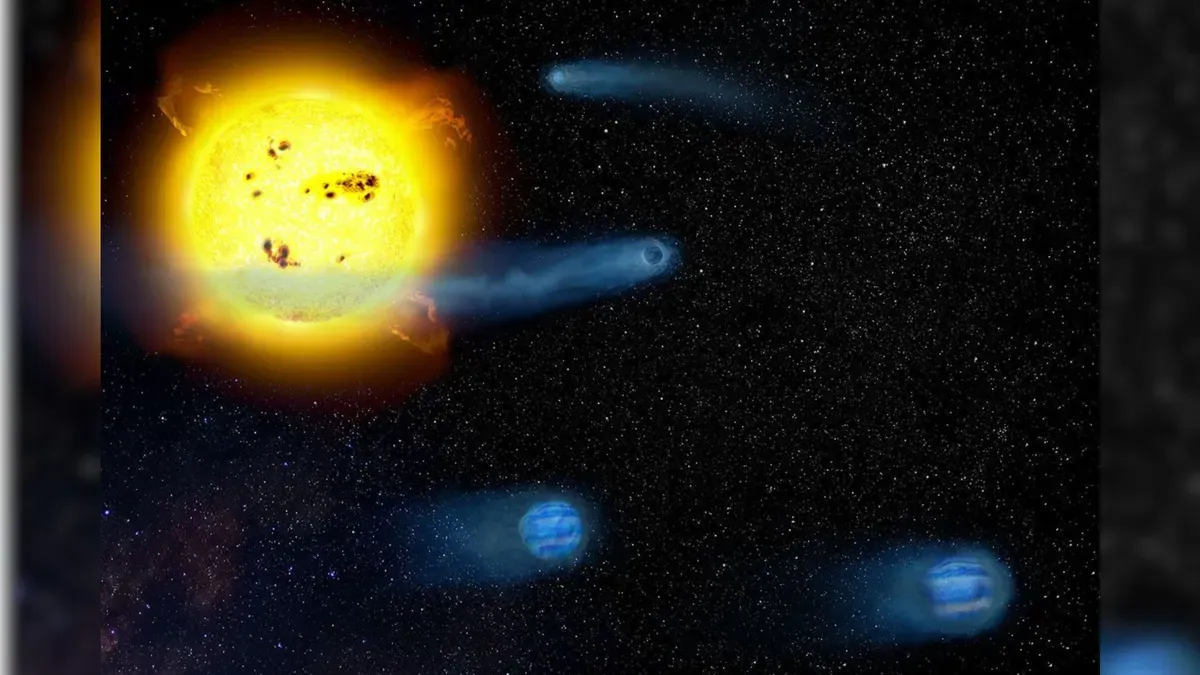

Astronomers have captured the first direct evidence of planetary evolution in action, revealing how the universe's most common planets are sculpted by stellar radiation.

The V1298 Tau system, 350 light-years from Earth, hosts four young planets orbiting a 23-million-year-old star. These planets, with radii 5–10 times Earth's but extremely low densities, provide a critical template for understanding the formation of 70% of known exoplanets.

Transit timing variations (TTVs) in the system allowed researchers to measure the planets' densities with precision. The low densities confirm atmospheric photoevaporation as a mechanism shaping super-Earths and sub-Neptunes.

Stellar radiation strips away planetary atmospheres over a 100-million-year timescale, with the inner two planets expected to lose their atmospheres entirely and become super-Earths. The outer two may retain partial atmospheres as mini-Neptunes.

Trevor David of the Flatiron Institute described the planets as exceptionally puffy, offering a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.

John Livingston of the Astrobiology Center noted that the four planets will likely contract into super-Earths and sub-Neptunes—the most common types in the galaxy.

The study highlights the role of orbital compactness in planetary system architecture, with closely packed planets experiencing accelerated atmospheric loss.

The V1298 Tau system's youth provides a rare opportunity to observe this evolutionary process in real time. By contrast, older systems show only the end results of such transformations.

The team emphasizes that further observations will refine models of photoevaporation rates and the transition between rocky and gaseous planets.